Did You Know?

For its remarkable restoration and adapted reuse, Shigar Fort Project won UNESCO Asia Pacific Award of Excellence for Culture Heritage Conservation in 2006

35°25'22.8"N 75°44'32.5"E

For its remarkable restoration and adapted reuse, Shigar Fort Project won UNESCO Asia Pacific Award of Excellence for Culture Heritage Conservation in 2006

The Best Time to Visit Gilgit Baltistan Region is Summers. Preferably from April to September. Winters are Extremely Cold and Snowfall blocks most of access. Hence Winters are not recommended.

Fong Khar, meaning ‘Palace on the Rock’ is the traditional name for the majestic 400 years old Shigar fort, lying in the heart of Shigar valley. It was built in 1634 by Hassan Khan Amacha, the Amacha Raja of Shigar. Fong Khar remained the seat of the Amacha Dynasty which ruled Shigar valley for centuries till its incorporation into the Dogra empire by General Zorawar Singh in 1842 AD when he conquered Skardu during Gulab Singh’s Reign. The fort lies in Shigar valley situated around 51kms from Skardu and can be accessed through Shigar road. The fort was restored as a heritage hotel by the Agha Khan Cultural Service in 2005, and for its remarkable conservation work, it was awarded the “UNESCO Asia Pacific Award of Excellence for Culture Heritage Conservation in 2006.”

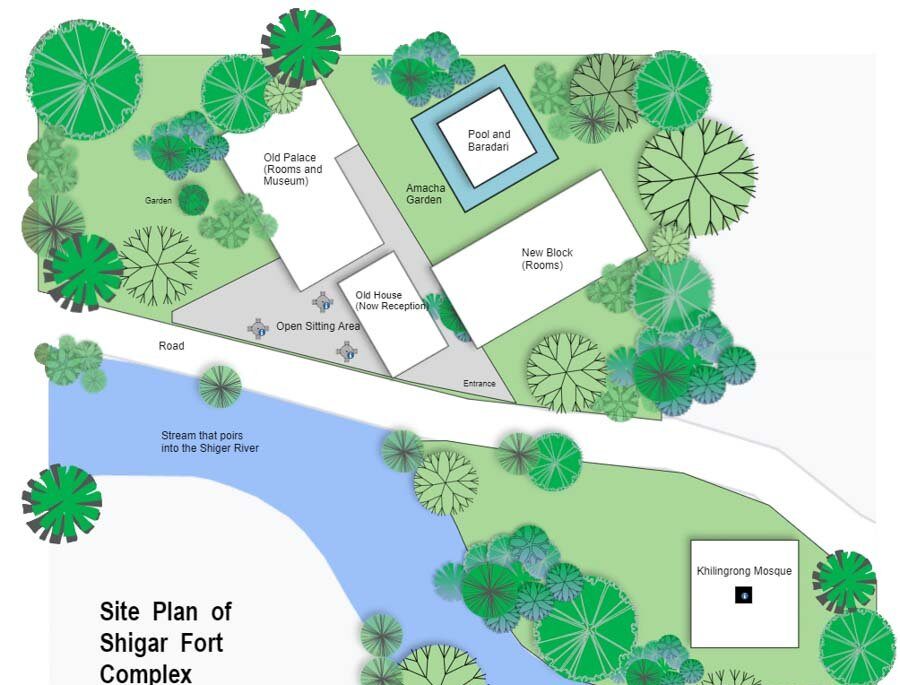

Interestingly, the fort derives its name‘ Palace on the rock’ from the fact that it was erected on top of a large conical boulder (rock), serving as a foundation for the entire edifice. On the southern side of the fortress lies a nullah (stream) which forms a tributary for the main Shigar river.

Shigar fort was constructed by Hassan Khan Amacha during the early 17th century after he prevailed over his rivals and became lord of the valley in 1634. Hassan Khan was the son of Mohammad Khan, who had twelve children, but Abdal Khan, the king of Skardu, had slaughtered eleven of Hassan Khan's siblings. Fearing the same fate, Hassan Khan escaped to Delhi and sought refuge and assistance from Shah Jahan, the Mughal Monarch of the time, who agreed to support the prince in his fight against Skardu's king, Abdal Khan. Hassan Khan returned with Mughal troops to Shigar, which aided him in capturing the crown. As a result, Shigar valley came under the suzerainty of the Mughal Empire, and a Mughal Thanedar also came to be stationed permanently at Shigar. Scholars believe that the old ancestral fort Khar-e-Dong was destroyed during the same military campaign. Following that, the foundation of the Shigar fort was laid down.

Shigar's Amacha family has a fascinating history. Ahmad Hassan Dani in his book “History of Northern Areas of Pakistan,” describes the story of the Amacha’s of Shigar. The history of this family is derived mainly from two sources: a 1752 AD Persian work of poetry called ‘Shigarnama’ written by the poet Sayyid Tahsin, who is also known for composing the work Diwan-i-Tahsin. The other source is the local legends and folklore which narrate accounts of the Amacha dynasty's rise to prominence. Traditions trace the foundations of the Aamcha Dynasty with the migration from Hunza valley to Shigar of a man named Shah Tham (or Cha Tham). If this narrative is correct, then the Amachas can be linked with the Trakhan dynasty of Gilgit .

The Amachas have ruled the Shigar valley since the 11th century and constructed other structures as well, but Fong Khar and the Khilingrong mosque are the only ones that have survived. The ornately designed Raja’s mosque, the Khilingrong Mosque, is a stunning monument erected about the same time in the early 17th century.

The Amacha Raja, who resided in the Shigar fort, used the mosque as his royal mosque. Remnants of an earlier structure can still be found about 600 feet above the level of Shigar Fort. These ruins belong to Khar-e-Dong, an earlier fort built by Amachas’ forefathers in the 11th century AD. There is believed to be a third structure belonging to the Amachas, known as Razi Tham Khar, although no trace or vestiges has been discovered thus far of this structure. Buddhist ruins have also been found in the proximity of the fort indicating the ancient makeup of the region.

The fort comprises three core clusters of structures or blocks that were constructed over the course of the fort’s three-century history. These additions also indicate distinct stages of architectural expansion in the original structure. The ‘Old Palace’ is the oldest and was the first edifice to be built on the enormous rock that gave the place its name. The ‘Old House’, which today serves as a reception and accommodates other services, was added later. Finally, the last structure to be erected was the block adjacent to the Amacha Garden. It now holds a number of guest rooms for the hotel (Please refer to the Site Plan of the Fort). During restoration work by the Agha Khan Cultural Service, the various Modules or clusters were adapted to fulfill various functions as required by the hotel's needs while keeping in mind the cultural & historical context of the spaces.

Shigar fort’s vernacular design heavily draws from traditional Tibetan, Balti, and Kashmiri architecture, and it employs a variety of indigenous construction techniques. Shigar Fort was constructed at a time when the Mughal Empire had just recently annexed Kashmir, hence Kashmiri influence on architecture was minimal. Kashmiri influence grew in the region after then. Shigar fort reflects a blend of architectural and artistic influences from Tibet, Ladakh, Central Asia, and Kashmir in its design. It also retains various traditional regional architectural elements such as shahnashins. These were recesses with three sides enclosed with walls and a wooden frame on the fourth, built to accentuate the sleeping area.

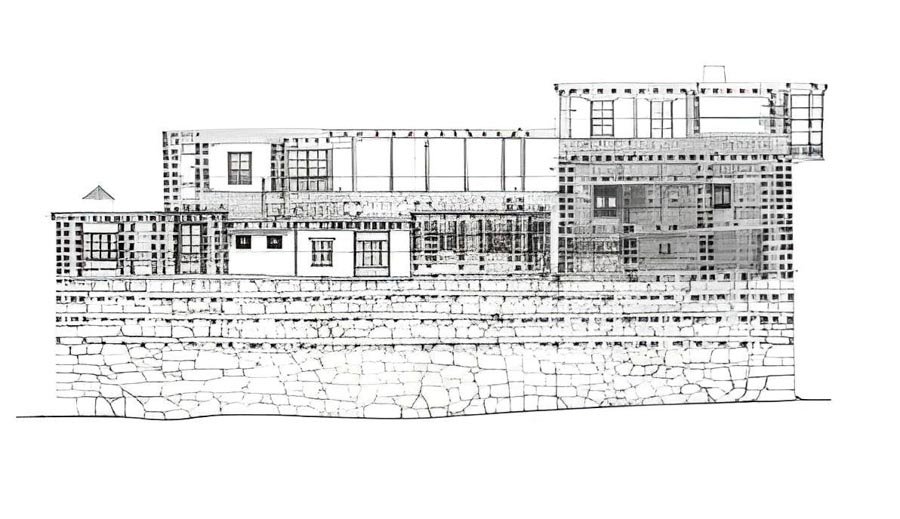

The fort stands firmly on a sturdy rectangular-shaped rocky base constructed in a form of stonework known as ‘Cyclopean Masonry,’ in which minimum space is left between the boulders, This stone base acts a ‘Motte’ for the fort with a height of roughly five metres ( sixteen feet). In medieval architecture, the ‘motte’ used to be a hill or an earth mound on which castles and forts were erected, offering additional security and increasing the defensibility of the fort and the inhabitants. This mott,e or the base, also encapsulates the massive rock forming part of this base, which probably fell from the nearby mountains. It is this conical shaped ‘Rock’’ from which the fort derives its name Fong Kar or ‘Palace on the Rock.’ (Refer to Drawing of Western Elevation of Shigar Fort).

The oldest section of the fort is the Old Palace, built in the early 17th century, and forms the original structure to be constructed on the Rock base and hence came to be known as Fong Kar. Over time, several extensions to the original edifice were made, including residential spaces and a modest personal mosque for the Raja and his family.

The exquisite Jharoka on the Southern Elevation is also part of the Palace. The palace's woodwork and ornamentations have strong Kashmiri and local inspirations, while the structure's form is influenced by Tibetan and local design sensibilities.

A photograph taken around 1900 AD of the fort shows the uppermost storey, which eventually fell into ruin and most likely collapsed. These upper storeys were not existent when the fort was restored in the year 2000.

To the south of the 'Old Palace' is the building 'Old House,' the ground floor of which was most probably built around the same period as or shortly after the Old Palace and served as the royal stable. When the use of the Old Palace was discontinued, the upper floor of this structure was added to act as a residential space, somewhere in the 20th century. Since its renovation, this structure has housed some guest rooms as well as the hotel's reception. On the western side of this structure, lies an open dining area with a restaurant where breakfast and dinner are served by the hotel management. With vines hanging from its half-covered wooden ceiling and a beautiful view of the mountain stream, the sitting area is fantastic.

The most recent addition to the fort complex is an elongated structure on the eastern side known as ‘Garden House.’ The building was added during the 1960s when the accommodation in the Old House needed addition. This served as the residence of the Raja and his family till 2004, when the complete fort complex was acquired by the Agha Khan Cultural Service for restoration. Raja and his family relocated to a new home just across the street from the fort.

The garden house hosts rooms which act as guest rooms for the Serena hotels. The northern edge of the structure opens into the Amacha Tsar (Garden), from where one can see the magnificent pond and baradari. Within the building, many traditional artifacts of Balti origin have also been displayed on walls to showcase the region's rich heritage. Spending a night in one of these rooms is a delight.When accessed from the entrance of the fort complex, this structure is positioned on the right side and features magnificent timber craftsmanship. On the lower level of this structure, there is also a small handicrafts shop where souvenirs can be purchased.

On northern side of the Amacha Garden, lies a beautiful pond with an equally exquisite Pavilion. A bridge connects the garden with the platform, on which the pavilion rests. According to Masood Khan, the time of construction of the pool is unknown. However, the pavilion was constructed by Raja Muhammad Azam Khan, during early 20th century, who was the father of the current Raja Muhammad Ali Saba. The garden with its pavilion in the middle of a pond, strongly resembles a Japanese Zen garden.

The fort was built using the ancient cator and cribbage system, which is still used in many regions of the Himalayas.“‘Timber lacing’, or the combination of cator and cribbage is a most sophisticated earthquake-resisting construction technique, finely demonstrated in the great monuments of Hunza and Baltistan.” This structural technique combines alternating layers of masonry and wooden logs, and it has proved to withstand earthquakes in seismically prone regions. “Thus the timber provides wall reinforcement and strong resistance against tension and bending, thereby complementing the qualities of stone or soil blocks that work well in compression. Reinforced concrete is but a modern version of this.” This technique, known as Kath Kuni in some parts of the Himalayas, is more than a thousand years old.

Roughly 300 feet from the entrance of the fort complex lies the Raja’s public mosque called Khilingrong mosque, an ornate wooden structure of considerable importance. Khilingrong Mosque’s intricate woodwork and elegant facade attest to the skill of the craftsmen who built it. Khilingrong Mosque was built during the same time as the Shigar fort, and the Raja who resided in the fort used the Khilingrong as his public mosque. There was a small private mosque for the Raja and his family within the fort as well. Restoration of the mosque was also undertaken by the Agha Khan Cultural service. Refer to Khilingrong Mosque for in-depth information.

Shigar Fort had fallen into decay over the ages, particularly the Old Palace, which went into complete degradation. Eventually, in 1999 the Raja of Shigar decided to donate the Shigar Fort to the Agha Khan Cultural Service Pakistan for restoration. AKCS-P is an arm of its international umbrella organization Agha Khan Historic Cities Programme, a renowned organization that has done incredible work in architectural conservation and restoration around the world. After hard work of five years, the restoration was completed in 2005.

The restoration project was conceptualized as a "catalyst" for sustainable development and economic revitalization for the Shigar area and its community. The project would be utilized as a public good, and a portion of its earnings would be spent back on the uplift of the local community. Around 20% of Serena hotel’s revenue established at Shigar fort is utilized to fund development works in the surrounding area through a local organization called ‘Shigar Town Management Development Society STMDS. This conservation model, which integrates cultural preservation and community development, provides a roadmap for comparable sites to follow.

'Adaptive reuse,' which conceptualizes the adaptation of historical sites for contemporary functions, is the philosophy underpinning the fort's restoration, and the historic site's newfound functionality fulfills a dual goal of conservation and utility. After 5 years of arduous effort and a cost of roughly US$1.4 million, the fort was restored and refurbished as a hotel run by Serena. Masood Khan, the project's principal architect, performed a remarkable job restoring this architectural marvel to its former splendor.

The structural conservation was done by a team led by Richard Hughes. In his paper, Richard Hughes describes the fort's withered state when the Agha Khan Cultural Service began renovation. He writes that when restoration began, “the palace was found to be highly decayed, considerably more so than any of the monuments so far conserved by the team… Many of the upper storey rooms were absent or half there, with evidence of rain-induced decay everywhere and fire damage at the south end. Many of the ground floor rooms were being used as animal byres… The rooms were basically bare of furnishings… and generally, there were odd bits of pots, broken lights, bits of wire, paper, and cars - all partly buried in dust and rubbish.”

Hence, it was a great architectural and conservation challenge to restore this structure and adapt it for a modern function. Some essential guiding concepts were followed during the restoration. To begin with, one of the most significant outcomes was the preservation of an architectural relic of significant heritage value in its most authentic form, which could only have been achieved by employing the same materials and design language as the original. Secondly, there was an attempt to preserve the physical as well the cultural functional structure of the building. There was a deliberate effort to stay as faithful to the actual functionality of the spaces as practicable. Personal quarters and sleeping areas of the fort were mostly retained as guest rooms for the hotel.

Finally, when it comes to designing the hotel's interior furnishings, the most essential principle was authenticity. Modern amenities were added without compromising the experience of the traditionally restored spaces. When examining the project's adaptive reuse potential, the project's financial viability and economic impact on the local community were also taken into account.

Shigar Fort was planned to be restored into a hotel with specific areas designated as a museum. The dual functionality would be achieved in this manner. Shigar fort's spaces were more ideal for this purpose than, say, Baltit fort, which had previously been restored solely as a museum. Masood Khan writes, “the reuse concept for Shigar Fort Residence strikes a balance between, on the one hand, a museal site (museum) and, on the other, a very special resort-type guest house offering the unique experience of authentic guest rooms in a historic palace).” The conserved audience hall in the Old Palace was converted into a museum for visitors with traditional exhibits and pieces of the preserved material culture of Baltistan. These exhibits have also been displayed in corridors of the hotel.

The structure of the building has been delicately preserved. “All deteriorated walls were opened up, and in certain instances realigned, both vertically and horizontally. Timbers that had rotted away or had been attacked by boring insects were identified and replaced. Anti-rot and insect repellent treatment was provided for the entire exposed timber structure. Timbers were pegged down again, particularly where the original pegs had rotted. Infill material (stone or earth block masonry) and wall renders were reconstituted where required, to accord with the original materia ”.

The historic palace has been rebuilt to function as a hotel as well as a museum. The Raja's private chamber has also been restored to its former splendor and is now offered for rent as the most expensive guest room. The main entrance has also been relocated, as the original old entry, which opened out to a big stairway, was identified. Ornately designed wooden architectural features were meticulously preserved and presented.

The Old House has been modified to accommodate a variety of service functions. On the wall facing the entryway, a reception counter has been set up. A modern restaurant and open seating area have been established on the western side of the Old house building. The hotel's garden house, which was once the Raja's residence, has been turned into guest rooms. Modern attached bathrooms have been inserted in the rooms with modern fittings. Rooms have been furnished with traditional hand-woven rugs, felt namdas and other textiles to create an authentic atmosphere. The lighting is low and atmospheric, complementing the fort's medieval mood.

Discover the Shigar Fort image gallery and immerse yourself in stunning photographs

All Photographs by Syed Noor Hussain and Sania Azhar.

All Rights Reserved. Photos may be used for Non-Commercial, Educational, Artistic, Research, Non-Profit & Academic purposes.

Commercial uses require licensing agreement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Build your travel plan and itinerary Dismiss

Heritage AI Assistant

Syed Noor Hussain

July 23, 2025 at 3:43 amBest