Protected Under

Antiquities Act 1975

31°35'14.2"N 74°18'54.3"E

![]()

On the UNESCO World Heritage Site List

Antiquities Act 1975

Lahore Fort’s Picture Wall is the world’s largest, spanning 1,450 feet and adorned with vibrant Mughal Era mosaics

The Best Time to Visit Punjab Province is Year long as it has bearable Cold winters and Hot Summers. However, Summers can get really Hot and precautions are recommended during Daytime visits.

The Lahore Fort, located in Lahore, Pakistan, is one of the most significant architectural achievements of the Mughal Empire. Serving as a fortified complex, it represents a culmination of various phases of construction and expansion carried out by successive Mughal emperors. Owing to its exceptional historical and architectural value, it is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list and is widely regarded as the most iconic monument in Lahore.

The origins of the Lahore Fort are closely linked with the early history of the city itself. According to local legend, the city was founded by Prince Loh, a figure from the Hindu epic Ramayana, and a temple dedicated to him exists within the fort’s boundaries. Archaeological evidence also suggests that the area was in use before the arrival of the Mughals, as coins from the Ghaznavid period have been discovered at the site. This supports the notion of an earlier structure, possibly a mud fort, existing prior to the Mughal period.

The recorded history of the fort begins with the conquest of Lahore by Mahmud of Ghazni. He appointed Malik Ayyaz as the governor of the region, and recognizing Lahore's strategic importance as a gateway to Central India, Malik Ayyaz established a fortification at the northeastern side of the city.

View of Deewan e Aam

View of Deewan e AamThis early structure, known as a 'Kacha Qila', was built from unburnt bricks. Some historical accounts suggest that an existing Rajput-era fort may have been present on a mound, which Malik Ayyaz later expanded or reinforced. During the Delhi Sultanate period, this fortification continued to be maintained due to the city’s strategic significance.

Following the Mughal defeat of the Lodhi dynasty in 1526, the region came under Mughal control. Mirza Kamran, the son of Emperor Babur, was placed in charge of Lahore and was responsible for commissioning the first Mughal architectural structure in the city—his Baradari, located on the banks of the River Ravi. However, the Lahore Fort in its present form began to take shape during the reign of Emperor Akbar. In 1566, he initiated the replacement of the older mud structure with a more permanent fort built from Lahori red bricks. This marked the beginning of the fort's transformation into a monumental architectural complex. Akbar also ordered the fortification of the city itself, leading to the establishment of what is now known as the Walled City of Lahore.

During Akbar’s reign, from 1583 to 1598, Lahore served as the imperial capital, prompting the construction of various facilities within the fort, including palaces and residences. Among the few surviving structures from this period is the Masti Gate (also known as Masjidi Gate), which faces the Mosque of Maryam Zamani, along with the fort’s original walls.

The Lahore Fort continued to evolve under successive Mughal emperors, each contributing new structures to the complex. Notable among these are the Diwan-e-Aam, Diwan-e-Khas, Sheesh Mahal, and the grand Mosaic Picture Wall. One of the most prominent additions was the Alamgiri Gate, constructed by Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir. This gate, facing the Hazuri Bagh and the Badshahi Mosque, serves as the main entrance to the fort and remains an enduring symbol of Mughal grandeur.

The fort’s location, outside the original boundaries of the Walled City and near the historic route of the River Ravi, provided it with an additional layer of natural defense. Over time, the fort continued to be used and modified even beyond the Mughal era. During British colonial rule, it was repurposed for military use, with various sections serving as barracks. These alterations were often done without regard for the architectural integrity of the site.

In the early 20th century, preservation efforts were undertaken by the Archaeological Department of India. Restoration work carried out between 1903 and 1924 aimed to conserve many of the fort’s structures and mitigate the damage caused by previous modifications.

The Lahore Fort today stands as a testament to centuries of architectural and political history, reflecting the layered legacy of empires that have ruled the region.

Fort were constructed in phases over different periods of its history. Built with burnt bricks, the walls feature large bastions placed at regular intervals, serving a defensive purpose. The fort is roughly divided into six distinct quadrangles, each representing a unique phase of its evolution. Many of the structures within these sections developed gradually over time. Key sections and features of the fort are outlined below.

Alamgiri Gate of Lahore Fort

Alamgiri Gate of Lahore FortThe Alamgiri Gate, an iconic feature of Lahore Fort, was constructed by the last great Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb Alamgir. Facing Hazuri Bagh and the Badshahi Mosque, the gate is flanked by two imposing towers, reflecting the grandeur of Mughal architecture. As one of the most photographed landmarks of the fort, the Alamgiri Gate stands as a powerful symbol of Lahore’s rich heritage.

Akbar’s Quadrangle is a vast open courtyard located on the southeastern side of Lahore Fort. While most of the structures in this area were replaced by subsequent emperors, one significant remnant from Akbar’s era remains—the Masti Gate. This gate, facing the mosque of Maryam Zamani (mother of Emperor Jahangir), derives its name from the Punjabi word Masiti, meaning mosque. Flanked by two massive bastions, the gate features a sturdy wooden structure reinforced with metal and adorned with metallic studs.

During the reign of Shah Jahan, the Diwan-e-Aam was constructed within Akbar’s Quadrangle. However, several original structures were removed during Jahangir’s rule to make way for his Daulat Khana-e-Khas-o-Aam, altering the quadrangle's original layout.

The Diwan-e-Aam, or Hall of Common Audience, was commissioned by Emperor Shah Jahan during the first year of his reign in 1631–32. Constructed in front of Akbar’s Daulat Khana-e-Khas-o-Aam, it served as a venue for the emperor to address public grievances and conduct state affairs.

This magnificent hall features 40 grand pillars and a central jharoka (balcony), where the emperor would make appearances before the audience. The structure, however, suffered significant damage during the Sikh War of Succession in 1841. It was later restored and reconstructed during the British era. During this period, the hall was repurposed as a field hospital when Shah Jahan’s Throne Hall was converted into a military barrack.

Jharoka of Deewan e Aam

Jharoka of Deewan e Aam

The oldest surviving structure in Lahore Fort, Daulat Khana-e-Khas-o-Aam was constructed by Emperor Akbar,and is located on the southern side of Jahangir’s Quadrangle. This historic building is documented to have had 114 rooms, with a marble balcony once used by the emperor. It was within this structure that Akbar celebrated Nauruz on December 29, 1587, marking its significance in Mughal history.

Jahangir’s Quadrangle, an expansive area located north of the Daulat Khana-e-Khas-o-Aam, features several remarkable structures and a distinctive Mughal Charbagh garden at its center. This quadrangle was initiated by Emperor Akbar and completed by his son, Jahangir, in 1618. While its foundations date back to Akbar, most of the existing structures reflect the architectural style of Jahangir’s era.

The central garden is designed in the traditional Charbagh layout, with a large water pool and a platform known as the Mahtabi in its middle. On the northern side of the quadrangle stands the Barri Khwabgah, or the Large Sleeping Chamber of the Emperor, which now houses a Mughal Gallery.

Adjacent to the Barri Khwabgah on its eastern side lies the Seh Dari, a structure named after its three (seh) doorways (dar), added during the Sikh period. In the southwestern corner of the quadrangle is the Shahi Hammam, or Royal Bath, another noteworthy feature of this historic space.

Barri Khwabgah in Jahangir's Quadrangle

Barri Khwabgah in Jahangir's QuadrangleWest of Jahangir’s Quadrangle lies the Moti Masjid Quadrangle, named after the exquisite Moti Masjid, or Pearl Mosque. This glistening white mosque, with its marble domes resembling pearls, inspired the design of other Moti Masjids built later, including those in Agra Fort by Shah Jahan, Delhi Fort by Aurangzeb Alamgir, and Mehrauli (Old Delhi) by Shah Alam Bahadur Shah. During the Sikh era, the mosque was repurposed as a treasury and briefly used as a mandir.

The quadrangle also houses the Dalan-e-Sang-e-Surkh and the Makatib Khana. The Dalan-e-Sang-e-Surkh, also known as Rani Jindan’s Haveli, is a two-story structure, with its upper storey added by Ranjit Singh for his wife, Rani Jindan. Today, this building serves as a gallery. The Makatib Khana, once used as a clerical workspace, is another prominent feature of this quadrangle, reflecting the administrative functions of the fort.

Shah Jahan’s Quadrangle, situated west of Jahangir’s Quadrangle, is home to several remarkable structures from Shah Jahan’s era. This quadrangle features the Diwan-e-Khas, Khwabgah-e-Shahjahani, Arz Gah, Lal Burj, and a central Charbagh garden.

On the southern side lies the Khwabgah-e-Shahjahani, also known as the Chotti Khwabgah. This structure comprises five spacious rooms, and its walls reveal stunning frescoes from the Sikh period, recently unearthed during conservation efforts.

The northern side of the quadrangle houses the Diwan-e-Khas, a magnificent white marble pavilion built by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1645. Adorned with intricate Pietra Dura inlay and elegant marble lattice (jaali) work on its northern side, the pavilion epitomizes Mughal architectural splendor.

Beneath the Diwan-e-Khas lies the Arz Gah, a space where the public would gather to present their petitions (arzaan) to the emperor, who would preside above in the Diwan-e-Khas. Together, these elements create a harmonious blend of administrative, ceremonial, and residential spaces, characteristic of Shah Jahan’s architectural vision.

Shah Jahan's Quadrangle

Shah Jahan's QuadrangleAdjacent to Shah Jahan’s Quadrangle lies the smaller Paeen Bagh Quadrangle, a space that includes several notable structures such as the Hammams (Baths), Paeen Bagh (Ladies’ Garden), Kala Burj (Black Tower), Khilat Khana, and a Zanana Masjid (Ladies’ Mosque).

The Paeen Bagh, or Ladies’ Garden, was a private garden reserved exclusively for the women of the royal harem, providing them with a serene space for leisure and retreat. Within this quadrangle, the Zanana Masjid, a mosque designed specifically for the women of the harem, offered a place for their religious observances. Together, these structures reflect the intimate and private aspects of life within the Mughal court.

Naulakha Pavilion

Naulakha PavilionThe Sheesh Mahal complex, a masterpiece of Lahore Fort, dates back to the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan and is celebrated as one of its most beautiful areas. Designed as a square courtyard, the complex features pavilions arranged symmetrically on all sides, with four shallow water channels dividing the courtyard into four sections. At the northern end stands the Sheesh Mahal, or Palace of Mirrors, an architectural marvel created by Shah Jahan for his beloved Empress Mumtaz Mahal, famously known as the Lady of the Taj. The hall is adorned with exquisite Aina Kari (mirror work), and its upper portion features intricate mosaics of glass set in gypsum.

Access to the Sheesh Mahal is through a grand arched gate, richly decorated with frescoes. In the northwestern corner of the complex lies the Athdara, an eight-door pavilion constructed during the Sikh period. Maharaja Ranjit Singh used this space to hold court, and its walls display remarkable Sikh-era frescoes depicting scenes from Hindu mythology.

On the western side of the complex is the iconic Naulakha Pavilion, named for its cost of nine lakh rupees. The pavilion is distinguished by its curvilinear Bangla-style roof, and its interiors are lime-plastered and adorned with frescoes.

The Sheesh Mahal is part of the larger Shah Burj area, which could be accessed directly from the outside via the Hathi Pol, or Elephant Gate. This stairway, consisting of 58 steps, connects the Hathi Pol to the outer courtyard of the Sheesh Mahal, adding an element of grandeur to its approach.

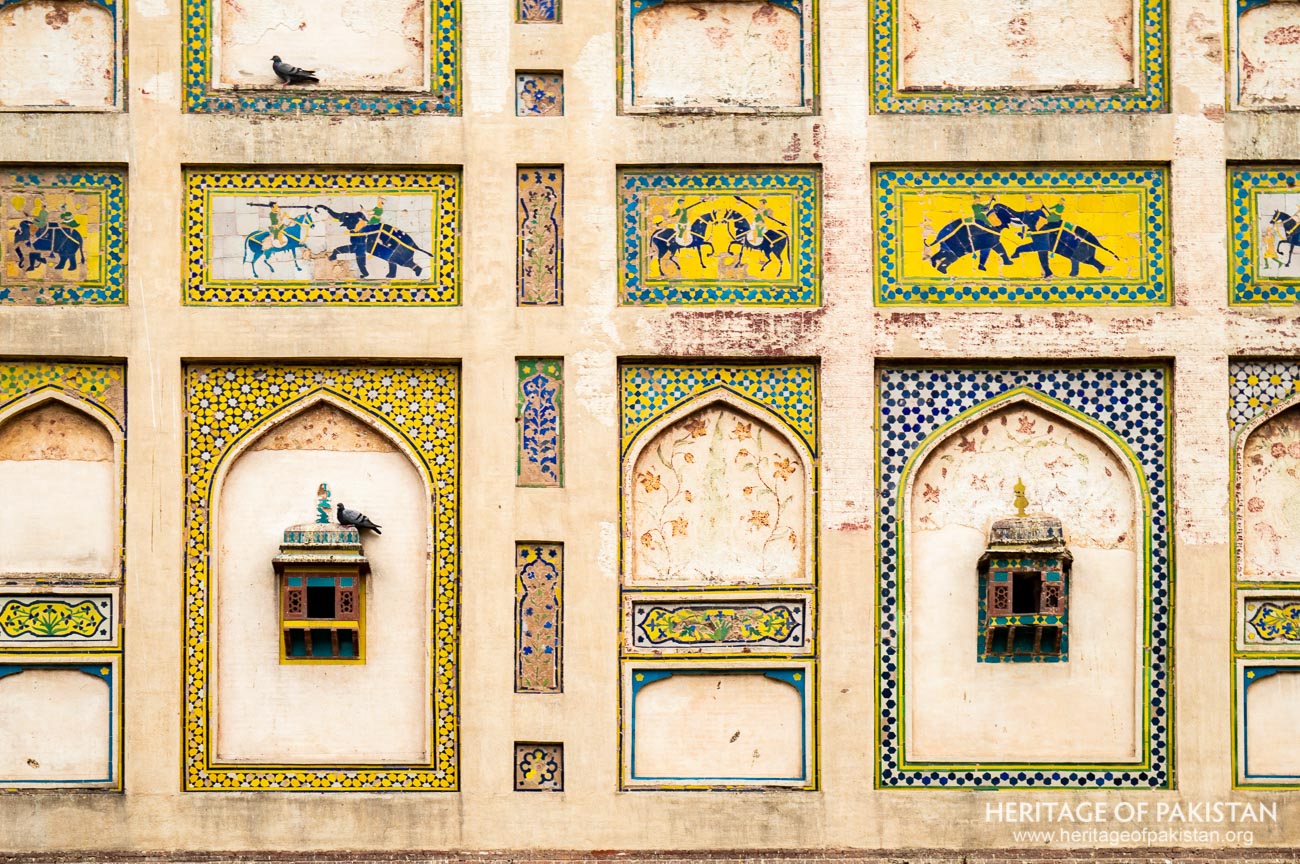

One of the most striking features of Lahore Fort is the Picture Wall, a masterpiece of mosaic tile artistry and pictography. Spanning approximately 460 meters along the western and northern faces of the fort, the wall stands nearly 15 meters high and covers a surface area of roughly 7,000 square meters.

The Picture Wall is adorned with a unique blend of geometric and foliated designs, as well as depictions of living beings—an uncommon feature in Islamic art. The vibrant mosaics illustrate elephants, horses, camels, men, and birds, showcasing the artistic and cultural diversity of the Mughal era.

Mosaic Picture Wall

Mosaic Picture Wall

Discover the Lahore Fort image gallery and immerse yourself in photographs

All Photographs by Syed Noor Hussain and Sania Azhar.

All Rights Reserved. Photos may be used for Non-Commercial, Educational, Artistic, Research, Non-Profit & Academic purposes.

Commercial uses require licensing agreement.

Add a review