Did You Know?

Wazir Khan served as the Royal Physician during Emperor Shah Jahan’s period

31°35'00.7"N 74°19'24.6"E

![]()

On the UNESCO World Heritage Site Tentative List

Wazir Khan served as the Royal Physician during Emperor Shah Jahan’s period

The Best Time to Visit Punjab Province is Year long as it has bearable Cold winters and Hot Summers. However, Summers can get really Hot and precautions are recommended during Daytime visits.

The Wazir Khan Mosque is a prominent Mughal-era structure situated near the Delhi Gate in the Walled City of Lahore. Constructed during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan, the mosque is widely regarded for its architectural refinement and artistic excellence, especially its vibrant and intricate Kashi Kari tilework. It stands today not only as a place of worship but as a lasting representation of the artistic and cultural achievements of its time.

The mosque was commissioned by Wazir Khan, whose real name was Ilm ud Din Ansari. He was born in Chiniot, where his father also belonged. Ilm ud Din initially studied philosophy and Arabic before travelling to Delhi, where he became a student of a hakeem to study medicine. His proficiency in the field led him to the court of Prince Khurram, who would later ascend the throne as Emperor Shah Jahan. Impressed by Ilm ud Din’s abilities, Prince Khurram appointed him Diwan, or superintendent of the household, and subsequently Mir Saman, the official in charge of the royal kitchen.

Upon Shah Jahan’s coronation in 1628, Ilm ud Din was further elevated. He was granted command over 7,000 soldiers and continued to serve as the Royal Physician, treating members of the imperial family. He was conferred the title of Wazir Khan and later appointed as the Governor of Punjab, a position he held from 1632 to 1639. During his tenure as governor, he undertook the construction of the mosque that now bears his name. A Persian inscription on the mosque’s entrance gateway dates its establishment to 1044 AH (1634 AD).

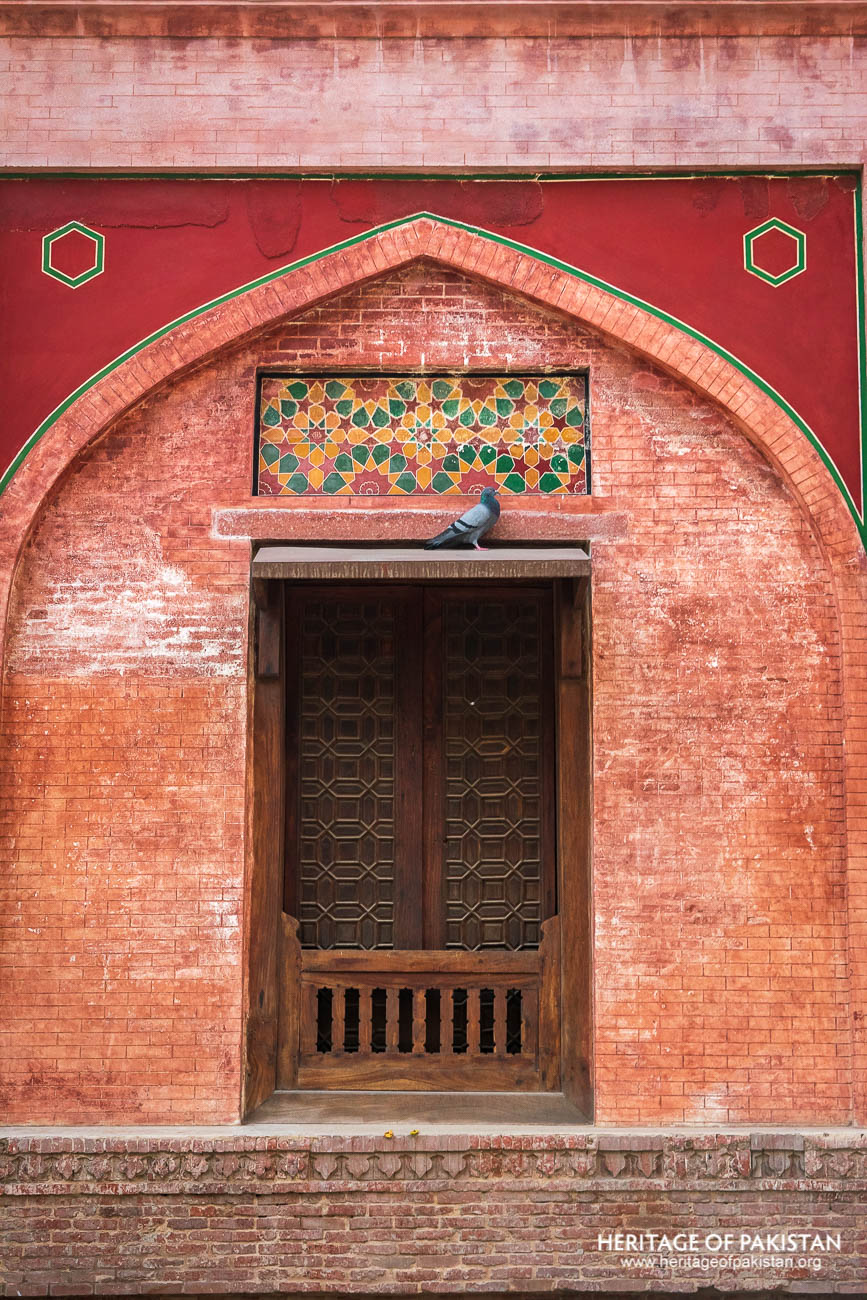

Entrance Gateway or 'Pishtaq' of Wazir Khan Mosque

Main prayer hall of Wazir Khan Mosque

The architecture of the mosque reflects a comprehensive approach to design and ornamentation. It displays a wide range of decorative techniques that were highly developed under Mughal patronage. These include tazakari (brick imitation work), naqashi (fresco work), multi-coloured Kashi Kari tilework, and calligraphy. The Kashi Kari, in particular, is notable for its use of eight distinct colours in glazed tiles, representing one of the finest applications of this technique during Shah Jahan’s era.

IH Nadeem has noted that the frescoes in the mosque are of the Buono type, a method in which paint is applied to fresh plaster. This allows the pigment to be absorbed deeply into the setting plaster, making the decoration an integral part of the surface and significantly increasing its longevity.

A poetic inscription on the main gateway offers a reflective message:

“In the corn field of this world, O well conducted man,

Whatever is sown by man, is reaped by him in the world to come.

In your dealings, then, leave a good foundation in the world.

For all have to pave their way to heaven through this gateway at last.”

The mosque has served not only as a religious structure but also as an artistic model. In his 1892 book, historian Muhammad Latif wrote that advanced students of the Mayo School of Arts were trained using design replications from the Wazir Khan Mosque. Over time, however, the physical condition of the mosque deteriorated and called for restoration efforts to preserve its intricate features.

Within the mosque’s courtyard lies the shrine of Syed Muhammad Ishaq, also known as Miran Badshah. This saint is believed to have come from Persia and settled in Lahore during the Tughlaq dynasty. His shrine continues to attract many devotees and remains a site of reverence within the community.

View of Wazir Khan Mosque from minaret

In 1051 AH (1641 AD), Wazir Khan created a trust and executed a waqf deed to ensure the long-term maintenance of the mosque. This deed was validated with the seal of Qazi Muhammad Yusaf, who was the Chief Qazi of Lahore under Shah Jahan. Through this legal instrument, Wazir Khan dedicated a significant portion of his property—from Delhi Gate to the mosque itself—for its support. The endowment included the Serai, the Shahi Hammam, as well as various shops and houses along the main passage. The income generated from these properties was to be used for the mosque’s upkeep. However, by the time of Muhammad Latif’s writing, most of the shops had been converted into private holdings, and the Serai and Hammam had come under government ownership.

Historian Nazir Ahmad Chaudhry recorded that according to local legend, artists from China were brought in to execute the mosque’s elaborate decorations. However, he clarified that there is no authoritative evidence to support this claim, asserting instead that the stylistic features of the work are of Persian origin.

Today, the Wazir Khan Mosque stands not only as a religious monument but as a cultural and artistic landmark that reflects the synthesis of governance, scholarship, art, and architecture during one of the most influential periods of the Mughal Empire.

Kashi Kari work of Wazir Khan Mosque

The Wazir Khan Mosque is a Mughal-era religious and architectural monument located in the Walled City of Lahore. Built during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan, the mosque reflects the Persian-Mughal architectural style and is widely regarded for its sophisticated craftsmanship and ornamentation. The overall structure, decoration, and spatial layout of the mosque serve as a significant representation of the Mughal period’s architectural excellence.

The mosque is laid out in a rectangular plan, with overall dimensions measuring approximately 280 feet by 160 feet. It is constructed on a raised plinth, with steps leading to its entrance. The entrance lies on the eastern side, in line with the typical orientation of South Asian mosques, where the western wall faces the qibla. The mosque is primarily built of brick and finished with smooth plaster. The external walls were painted red using the true fresco technique, with a carved brick pattern applied to imitate the appearance of real bricks.

Main prayer hall of Wazir Khan Mosque, Lahore

Fresco work of Wazir Khan Mosque

The mosque showcases a wide range of decorative techniques developed and refined under Mughal patronage. These include tazakari, which refers to brick imitation work; multi-coloured Kashi Kari tile work; naqashi or fresco painting; and ornamental calligraphy. The tile work in particular is executed using the mosaic technique, in which individual coloured tile pieces are cut into precise shapes and embedded into mortar. This method differs from the painted tile technique, where tiles are painted and baked in predetermined forms before being assembled onsite. The fresco painting used throughout the mosque is of the Buono type, as noted by IH Nadeem. In this technique, paint is applied to fresh plaster, allowing it to be absorbed deeply into the material, becoming an integral and long-lasting part of the wall surface.

The entrance to the mosque is marked by a grand pishtaq and arched iwan, characteristic features of Timurid architecture that were later adapted by the Mughals. The gateway is elaborately decorated with Kashi Kari, arabesques, floral and geometric patterns, and intricate calligraphy.

Minaret of Wazir Khan Mosque

An inscription on the gateway features the Kalma along with the Hijri date of the mosque’s completion. Above the main entrance, the inscription reads, “The noblest of the recitals is: There is no God but God, and Muhammad is the Prophet of God.” To the right of the Kalma is a smaller inscription that states, “Constructed during the reign of the valiant king, the lord of constellation, Shah Jahan.” Below this, another inscription acknowledges the founder with the words, “The founder of this house of God is the humblest of old and faithful servants, Wazir Khan.”

The gateway leads into a domed entrance hall, flanked on both sides at an upper level by projecting jharokas. The entrance opens into a large central courtyard, the focal space of the mosque. At the center of the courtyard lies a large pond used for ablution or wuzu. Each of the four corners of the courtyard is anchored by a tall minaret. These minarets are intricately ornamented and are crowned with chatris—domed kiosks in the form of small pavilions. The minarets are structured in three vertical segments. The lowest segment or base is square-shaped and includes proportionally distributed niches on each face. Above this, the middle section transitions into an octagonal shaft. The upper portion of this shaft is divided into sixteen decorated panels, many of which feature tree motifs. At the junction between the shaft and the chatri is a pendentive structure known as alub kari. Internal staircases within the minarets provide access to the top, from where one can observe a panoramic view of the Walled City of Lahore.

The main prayer hall is situated on the western side of the courtyard. It features a central pishtaq with an arched entrance that is flanked by two smaller arches on each side. The façade of the prayer hall is capped with a continuous mudakhal pattern forming a decorative parapet. The hall is topped with five domes that correspond with the five arches of the façade. Among these, the central dome is slightly elevated above the flanking domes. The architectural design employs the four-centered flat pointed arches that were commonly favored in Mughal construction, offering a subtler and flatter profile compared to the sharp two-centered arches characteristic of Gothic styles. The spandrels of these arches are elaborately adorned with decorative detailing.

Inside, the prayer hall is richly embellished with fresco painting that extends the mosque’s tradition of intricate interior design. The flooring has been artistically paved with geometric patterns that contribute to the overall visual harmony of the space.

Along the enclosure walls are rows of hujras or cells that historically served as spaces for the practice of artistic trades and as rooms for madrassa-based religious instruction. The western section of the mosque also includes a number of shops that have since been restored and repurposed for various contemporary uses.

John Lockwood Kipling, who served as the Principal of the Mayo School of Arts (now the National College of Arts) and Curator of the Lahore Museum, once remarked on the artistic value of the mosque by stating, “This beautiful building is in itself a school of design.” His observation underscores the mosque’s historical role as both a spiritual sanctuary and a vibrant center of artistic heritage.

Discover the Wazir Khan Mosque image gallery and immerse yourself in photographs

All Photographs by Syed Noor Hussain and Sania Azhar.

All Rights Reserved. Photos may be used for Non-Commercial, Educational, Artistic, Research, Non-Profit & Academic purposes.

Commercial uses require licensing agreement.

Add a review